Artists borrow material to create new art. This practice is widely acknowledged and condoned in art circles. Daniel Grant makes this point in a recent Wall Street Journal article. Mr. Grant also points out, however, that copyright law can potentially render artistic borrowing an unlawful transgression. What is routine practice in the arts may lead to litigation and an intellectual property minefield.

Mr. Grant’s article discusses the Rogers v. Koons case. In that case the renowned artist Jeff Koons was sued by photographer Art Rogers. Mr. Koons made an unauthorized sculptural and literal rendition of a photograph taken by Mr. Rogers that depicted a family with eight puppies. A federal court found that the sculptural representation amounted to copyright infringement. Mr Koons unsuccessfully argued that creating the sculpture from the photograph was a transformative social commentary. This type of commentary, he argued, was an important artistic activity. It was a good argument, but not a legally persuasive one.

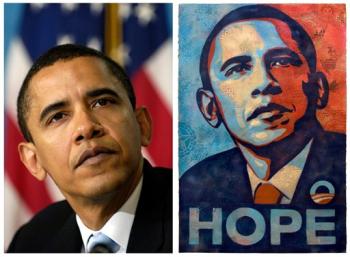

The Rogers v. Koons case was decided in 1992. Seventeen years later, a very similar case is now publicly unfolding. This case also involves an artist and a photographer. In this case, the artist is Shepard Fairey, who created the Obama Poster shown below from a photograph taken by photographer Mannie Garcia. Mr. Garcia, who is a freelance photographer, was working for the Associated Press at the time he took the photograph, shown below next to the poster image. Mr. Fairey based his image on the photograph without asking the Associated Press for permission. Now, Mr. Fairey has sued the Associated Press to have the copyright issue resolved.

The question, however, remains contested. How can one determine if their new work has unlawfully copied another work? How much borrowing is permitted? Prior cases, like Rogers v. Koons state that an original work is copied when “the accused work is so substantially similar to the copyrighted work that reasonable jurors could not differ on this issue.” That is a fuzzy boundary that is determined on a case-by-case basis.

So here’s my question: